The riddle of the heath

Royston Heath is a riddle.

This strangely-shaped piece of wasteland stretches east to west over the OS Map like a sleek cat stalking a stray town-rat. On the ground it seems huge but, from its eager head to the tip of its tail, it measures just 21/2 miles. If you’re lucky enough to view it from the front seat of one of the biplanes that regularly buzz Royston from nearby Duxford, the heath looks tiny.

Perspective is everything.

Though the cat nuzzles up close to the town, a parish boundary means this is Therfield – not Royston – Heath. A century ago the Victoria County History (1912) proclaimed it the ‘recreation ground of the town’.

Look a little closer and you will discover something far more intriguing.

Not that that matters to most people who (like my friend Peggy) come out every day to walk their dogs, support the footballers or rugby team, fly kites with their kids, go jogging or toboggan down the hills, slicing through winter snow.

Bee Orchid, Therfield Heath (copyright Graham Palmer 2017)

English Heritage says the Heath is ‘one of the best surviving prehistoric landscapes in the region’ and Natural England that this small plot of land nurtures ‘some of the richest chalk grassland in England’. It is the last tattered remnant of an open heath that bordered the ancient Icknield Way and was littered with hundreds of prehistoric burial mounds (now ploughed out), a borderland where the chalk hills rose up and, at Royston, confronted the low marsh of Bassingbourn Fen.

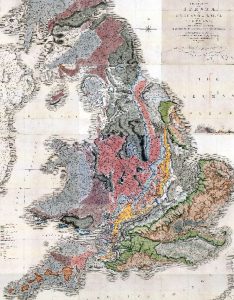

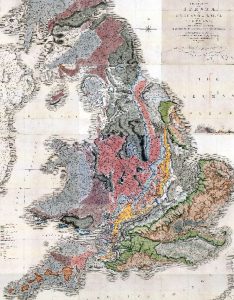

On his Great Map (1815), the geologist William Smith marked the Royston Downs as stretching from Newmarket to Dunstable, edged by the clays, gravels and sand of Cambridgeshire and Bedfordshire.*

When so much historic and ecologically important heathland has vanished, how on earth has Therfield Heath survived?

To answer that riddle you must go back to the time of the Anglo-Saxon invasion. These incomers held everything they seized (including the former inhabitants) as common property and soon established vills across the country. Land was not ‘owned’ as we understand the word, but the householders were granted rights to use it. In return, they were expected to fulfil communal duties (house-building, service in the militia etc) and support the king’s court with food rent. Disputes were settled by custom or consensus at a moot (village meeting) and the village granted each householder a house, kitchen garden and strips to cultivate in the shared open fields.

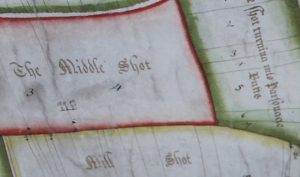

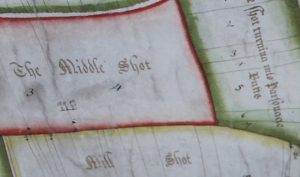

At ðereuelde the open field was portioned into named ‘shots’ (from the Old English sciat, meaning a nook or corner) and these were divided further into strips. A huge and beautifully drawn map of the Therfield Common Field (1725) shows that many of these Anglo-Saxon shots survived for centuries and lists their intriguing names: Cats Holes, Claw Buck Shot, Chalky Dane Hill, Tumbelow Shot and over a hundred more. The map’s most noticeable feature is a very large splat of bright green paint, indicating the open grazing land that is now the Heath.

The idea of land ownership only developed over the next five hundred years as Anglo-Saxon kings passed their right of local food-rent to the new monasteries and abbeys which grew up with the conversion of the country by Christian missionaries. This accumulation of wealth did not go unnoticed by the Vikings and led to many bloody clashes, culminating in the eleventh century with an invasion from Scandinavia that put the Danish Cnut on the English throne.

One legend from those days centres on the humble Pasque flower, a purple gem that still flourishes on the Heath. The tale goes, it only thrives where Viking blood was spilt. True or not, in Therfield it was a Dane who first staked a claim to own the heath. The local reaction was predictable…

–

Much further north, on a island in the marshes at Ramsey, an abbey had been established. In the same year that the abbey church was completed (974) a terrible earthquake shook England, bringing down houses. The quake – or simple subsidence – weakened the building and within ten years major cracks appeared. After much soul-searching, the monks were forced to tear down the church’s central tower and rebuild it. Fortunately, the problem did not affect the church’s west tower which housed a light that guided people in across the marsh and the bells that signalled the changing Holy Hours and were believed to echo God’s voice.

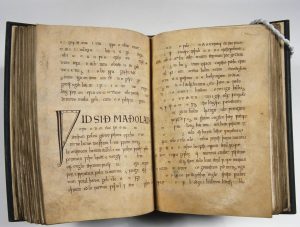

The abbey’s monks lived their lives according to St Benedict’s strict rule which emphasised stability, conversion of manners, and obedience. Boys from respected families were taken in and educated there but it was difficult for some to adjust to the ways of the cloister. The Chronicon Abbatiae Rameseiensis (The Ramsey Abbey Chronicle) records how one boy proved a particular challenge.

Etheric was still young when sent to Ramsey and he and three playmates – Athelstan, Eadnoth and Oswald – soon fell foul of the abbey’s rules. One day they got it into their heads to sneak up the west tower. Who touched a bell rope first? When the bell rang out there was no way back. Egging each other on, the boys became more and more exuberant.

Now bell ringing is an art. Done wrongly it can cause all sorts of trouble and, at the height of ensuing cacophony, Etheric’s bell cracked. The boys were shocked, the monks furious. They wanted the culprit flogged but the Abbot held his hand, realising that Etheric and his friends were truly sorry and more good might come out of their penitence. He was proved right as all four went on to become pillars of the Church: Oswald became a monk and poet, Athelstan succeeded as abbot, and Eadnoth and Etheric became some of the most powerful clerics in England. As Bishop of Dorchester, Etheric commanded King Cnut’s ear and was to reward the abbey with untold riches, including the vill and lands of Therfield which were currently held by a Dane…

–

The Danish settler was not very comfortable in his possession. In fact, he was in fear of his life. There were bandits in the area and villagers had taken so badly to his ways that the Dane could not sleep unless four men were standing guard nearby. The Ramsey Abbey Chronicle tells how, one night, he overheard his guards plotting to kill him. If they could not hand him over to the bandits, they swore they would relieve the village of his abominable existence by sticking a knife in his bowels.

A later portrait of Cnut the Great.

That night the terrified settler crept away to the safety of his a friend’s nearby vill. Punishing the guards was not an option as the villagers would retaliate and it would be impossible for one man to evict a whole village. The Dane had no choice but to make his way to London to consult the king.

In the meantime, Etheric’s local agent (apparently based at Ashwell) got word to him about the trouble and Etheric, who was in London, persuaded both Cnut and the settler that the land was worthless while the villagers were in rebellion. The obvious face-saving solution would be for Etheric to buy the land (at a knock-down price) as a gift for the Abbey at Ramsey in recompense for a broken bell.

–

Therfield (and its heath) remained with the monks at Ramsey right up until the mid-sixteenth century when Henry VIII dissolved the Abbey and seized all its lands. The manor passed briefly to Katherine Howard as part of her marriage settlement but within thirteen months she had been beheaded and it reverted to the king. Two years later he exchanged it for lands held in Essex and Middlesex by the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s and for the next four hundred years the Church of England held Therfield in its possession.

Enclosure came to the open fields in the mid-nineteenth century but the green splurge on the 1725 map was retained as common grazing, the site of Royston town gatherings, celebrations, fairs and the occasional prize fight.

Racehorses on Therfield Heath (Copyright Graham Palmer 2017)

The management of the heath – with its various petty disputes – proved increasingly troublesome to the Church Commissioners who felt ownership should pass to a body more in tune with local needs. By the 1890s a body of trustees (or Conservators) made up of Royston rate-payers and wealthy local land-owners, who retained rights to graze their sheep, took control of the Greens of Therfield and its Heath. ‘The Award’ also enabled John Francis Fordham of Thrift Farm to exchange an isolated patch of land he owned in the centre of Therfield to create a playing field in return for which he got the part of the Heath between his farm and what is now the A505, lopping off part of the cat’s tail and substantially altering the boundaries of the ancient grazing land for the first and only time.

Students from Cambridge had briefly established a golf course on the Heath years earlier but it was not till 1892 that Royston Golf Club was formed. The Conservators now maintain the Heath using money earned from renting out large parts of it to the golf club and the horse-training gallops.

*Published in 1815, it was the first geological map of Britain and the subject of the bestseller The Map that Changed the World. An original hand-coloured map is on display at the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge and a replica can be seen at the Natural History Museum, London.

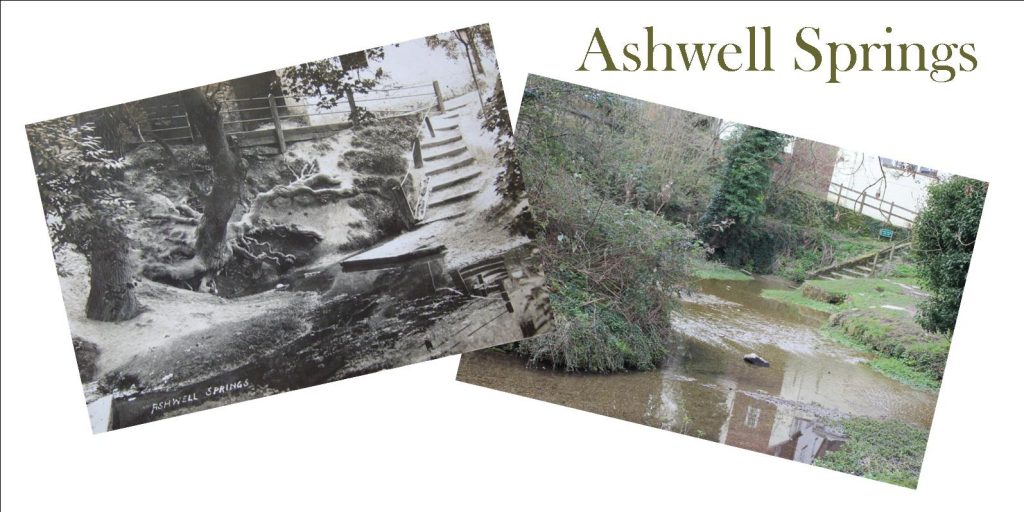

It was not so long ago that such springs and ponds were considered sacred and were even, on occasions, known to yield treasure (old votive offerings from long dead people to the water-giving spirit or god). Perhaps this is why the shallow dew pond (now vanished) which watered animals at the foot of nearby Therfield Heath was once known as the Golden Bog. No treasure survives there now, just a patch of dry nettles thriving on soil enriched with the manure and sediment from the pond’s bottom.

It was not so long ago that such springs and ponds were considered sacred and were even, on occasions, known to yield treasure (old votive offerings from long dead people to the water-giving spirit or god). Perhaps this is why the shallow dew pond (now vanished) which watered animals at the foot of nearby Therfield Heath was once known as the Golden Bog. No treasure survives there now, just a patch of dry nettles thriving on soil enriched with the manure and sediment from the pond’s bottom.

This Roman goddess had a penchant for creative destruction which stemmed back to her strange birth. She had been born from the union of Jupiter (the sky-father who carried a thunderbolt) and a female titan. When the titaness fell pregnant the prospective father was not overjoyed because it had been prophesied that his own child would eventually overthrow him. His solution was to swallow his lover whole before she could give birth. Trapped inside Jupiter, the titaness set about forging weapons and armour for her soon-to-be-born daughter. The stress and the racket of his ex-lover’s new hobby gave Jupiter such a migraine that he persuaded Vulcan to split his head open with a hammer and, lo-and-behold, out of the cleft jumped Minerva, fully-grown and armed to the teeth. But Minerva was destined to become a goddess of wisdom as well as war, so she made things up with her father…but that’s another story.

This Roman goddess had a penchant for creative destruction which stemmed back to her strange birth. She had been born from the union of Jupiter (the sky-father who carried a thunderbolt) and a female titan. When the titaness fell pregnant the prospective father was not overjoyed because it had been prophesied that his own child would eventually overthrow him. His solution was to swallow his lover whole before she could give birth. Trapped inside Jupiter, the titaness set about forging weapons and armour for her soon-to-be-born daughter. The stress and the racket of his ex-lover’s new hobby gave Jupiter such a migraine that he persuaded Vulcan to split his head open with a hammer and, lo-and-behold, out of the cleft jumped Minerva, fully-grown and armed to the teeth. But Minerva was destined to become a goddess of wisdom as well as war, so she made things up with her father…but that’s another story.