As a follow-up to my post on naming things, I thought it might be fun to have a brief look at three intriguing place-names from the area that provides the backdrop to our Cracked Voices project…especially as they are a bit of a riddle and involve chiefs, gods and a very slight whiff of controversy.

–

Therfield (home to an unwelcome Viking)

The name Therfield has developed over time from ðereuelde to Thyrefeld to Tharfield and can be interpreted in at least three different ways.

At the time of the Domesday Book it was known as ðereuelde / Furreuuelde, which can mean ‘village of the furrowed fields’, hinting at the tantalising possibility that the strip lynchets (terraces) cut into the chalk scarp of Fordham’s Wood (at Scald Hill East and West) and also to the west at Scald Bank predate the Norman invasion and may go far much further back to the time of the builders of the prehistoric barrows which litter Therfield Heath.

Scald Bank

Image © Graham Palmer 2017

The second interpretation is…well, a bit boring! It is a very dry place (the only water came from the village’s ancient man-made ponds) and it is the highest point for miles (and used to host one of the county’s three beacons). This is the ‘village of the dry (or high) field’.

The third is based on the fact that Norman scribes often changed the Old English y into e when they were writing things down. ðereuelde might really be Thyreuelde, meaning Thyra’s Field. Now Thyra is a Viking name and the feminine form of Thor, whose Anglo-Saxon equivalent was the god Thunor. Given that flint (which abounds in the local fields) was intimately associated with the god of thunder (a subject I will return to in a later post), this may not be so far-fetched…especially as more than one thunderbolt (flint axe) has been found locally.

Thriplow (home to a Bronze Age chief)

It is thought that that the name of Thriplow (more correctly pronounced Triplow) has much simpler origins.

Thriplow Village Sign

In the Domesday Book it is Trepeslai (or, substituting y for e, Trypeslai). The lai (or low) came from Old English hlaew meaning barrow or round mound. Like Therfield Heath, the area was rich in prehistoric barrows (at least fourteen, now all ploughed out) including the nearby Chronicle Hills and Tryppa’s barrow which stood to the south east of the Parish Church. Tryppa is believed to have been the name of an ancient chieftain who at one time lay buried in the barrow. In the 1780s Dr Bernard ‘attacked this tumulus…with ten men’ and apparently found nothing. In the 1840s Richard Cornwallis Neville (the man behind Saffron Walden Museum) reported that there were still persistent rumours that two Bronze Age swords had in fact been discovered but, sad to say, they have never been heard of since.

Royston (home to a rather peculiar stone)

Royston, where a trackway (now the dual carriageways of the A505) crossed the Roman Ermine Street (the A10), is unusual in that it was not recorded in the Domesday Book. The question is, did it exist? At the time it did not have its own parish or manor so, for tax-raising purposes, it is just possible that any settlement at Royston was considered irrelevant by the Domesday information-gatherers. Certainly, both Baldock and Therfield were far more significant, but the important crossroads must surely have been marked in some way.

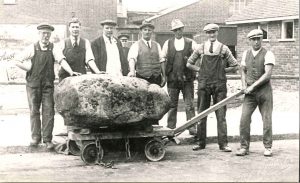

The enigmatic Roysia Stone at the heart of Royston

In other place-names ton often just denotes a settlement (from the Middle English toun). Here the Roys may refer to a wealthy woman named Roysia who was believed to have erected a cross, on top of the large boulder known as the Roysia Stone. That was certainly the belief of the historians writing in Elizabeth I’s time but it is questionable whether the indentation on the top of the stone is deep enough to hold a cross steady. Similarly, though the first known reference to the place (1184) is as Crux Roaisie, the Crux may simply refer to the crossroads which is still known as the Cross.

The work of a seventeenth century Danish antiquary (with the wonderful name of Olaus Wormius) may throw some light on the town’s name. He described an ancient tradition of cremations (or roiser) and how the ashes were buried in an earth mound (or roise). Given the number of prehistoric burial mounds on the nearby Heath, some historians have questioned if the Roysia Stone (in Middle English stone is stōn) may have once stood on its own mound at the crossroads.

Moving the Roysia Stone (Photo courtesy of Royston Museum)

The stone is strange in itself. As there is no other rock of its size for miles around, it would have held special significance for early man, and it is no accident that it became a waymarker on the Icknield Way. It started off somewhere in the Pennines and was carried to Royston by a glacier during one of the Ice Ages but there is no evidence as to where it initially came to rest. Wherever it was, in June 1786 we hear of it being moved from the crossroads to Market Hill and since then it has been moved three further times. It currently sits on a plinth to the south side of the crossroads, surrounded by benches and remains the enigmatic heart of the town.

–

With such ancient riddles to build on, it is not surprising that the area has thrown up a whole mound of stories…just a few particles of which are going to form the basis for Cracked Voices.