Our call for performers is now live! We’re looking for a soprano, a baritone, a pianist and a clarinettist to perform Cracked Voices in 2018. For more details please see the call page.

Our call for performers is now live! We’re looking for a soprano, a baritone, a pianist and a clarinettist to perform Cracked Voices in 2018. For more details please see the call page.

The second song in the cycle is Three Riddles – effectively three art songs in one. As each section has its own riddle attached, I felt it necessary to consider a separate musical riddle to attach to each section too.

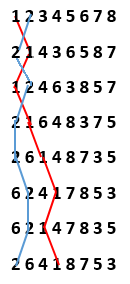

As it happens, my musical past happens to include a few oddities that don’t crop up in your standard composer’s biography. One of those is that from 2010 to 2014 I did quite a bit of church bell ringing. This all came about because my husband is a ringer (and a good one at that!), and his tower needed learners for their trainee teachers to practice on. I was never particularly good, especially as I couldn’t attend practices regularly after my daughter was born, but I’ve always found method books fascinating. For those who are unaware of these, they are books full of lots of numbers and squiggly lines, such as this:

A while ago while perusing ringing methods (as you do!) I stumbled across Royston Delight Major. Ringing methods have quite strict nomenclature – Royston is the name of the method, while Delight specifies the way the method is called and Major means eight bells are used. Eight bells you say? In a major scale? That seems like a perfect opportunity…

Keep your ears peeled for this appearing in a clarinet part sometime in March 2018! There’ll also be another bizarre reference in the third of the Three Riddles..

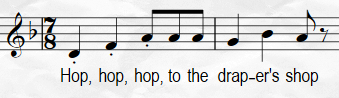

From ringing methods to some music theory (less odd). I’m a fan of theory, and I love going a bit mad over it with my students (though they don’t often share my enthusiasm!). To be brief: A fifth is the interval between a C and a G on the piano, and is the most consonant and pure interval other than an octave. The most common modulation (key change) is that of a fifth. If you move around the scale through fifths, it creates a closed circle and you arrive back where you started:

D – A – E – B – F# – C# – G#(Ab) – Eb – Bb – F – C – G – D

Often a piece will use a section of the circle of fifths, or modulate one way or the other. In my organ piece Circular Musings I modulated through the whole circle in one piece, in four/eight bar chunks. For the riddle, I wanted some accompaniment to juxtapose a section of text talking about footing being sound, trembling foundations and rebuilding. When you only take one or two steps along the circle of fifths, it can sound very strong, but to continue moving round it continuously can feel a little unsettling until the music pauses and grows some roots.

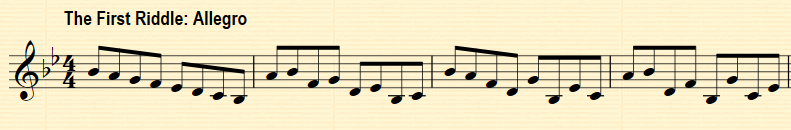

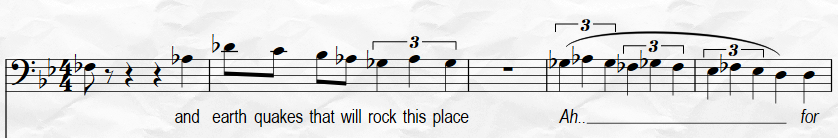

Here’s the bass line of the piano for this section of the piece, which starts on D and cycles round the fifths (well, in this case, inverted fifths!) until it arrives back at D:

As to what the right hand and baritone are up to at the time.. you’ll have to wait and see!

We’re excited to announce that Jenni has been named a grantee of the PRS Foundation’s Open Fund for Music Creators. This further funding for Cracked Voices will help support the project in general, but in particular the second performance and a studio recording! Thank you!

Graham and Jenni were on BBC Three Counties Radio today, talking to Nick Coffer about all things Cracked Voices. As well as talking about the project and some of the characters involved they talked about their call for people to submit ideas for the final song! There was also an excerpt of the first performance of The devil and the draper/Sidney Powell’s shindy, which was premiered last summer by Meridian School’s choir.

Listen again on the BBC iPlayer website here. Graham and Jenni are on from 1h44 (and the Meridian Choir shortly after!).

Graham and Jenni will be on BBC Three Counties Radio this Wednesday (24th May), talking about Cracked Voices and the recently launched Your Voice call for forgotten people! They’ll be on with Nick Coffer at about 1.30pm. Tune in to hear more about the project!

Computer programmes and video games often include Easter eggs – little intentional secrets, inside messages or secrets to be found by the users and players. I’ve always thought of word painting (in the musical sense!) somewhat in the same way.

When related to text, word painting is all about the use of highly descriptive words to invoke images into the reader’s mind. Musical word painting is the equivalent using notes – Grove Music defines it as “The use of musical gesture(s) in a work with an actual or implied text to reflect, often pictorially, the literal or figurative meaning of a word or phrase”. It can be found across the musical spectrum, though commonly in Renaissance and Baroque music, art songs (aha!) and folk music such as madrigals. Sometimes a motif representing a mood – e.g. grief – may be the basis a whole piece revolves around, and in others it can be a fleeting gesture supporting the text.

Some musicians, composers and musicologists shy away from word painting, thinking of it as a bit childish and simplistic. However, I personally think of it more as human nature. Think of a sentence with the word “falling” in it. Say it out loud a few times. Does your intonation rise or fall on that word? It seems to me it falls the majority of the time when I say it – or am I just word painting with my speech too? (I’ve always waxed lyrical about how musical speech is!).

I like adding in moments of word painting. I particularly like a phrase where you have a melody established (and potentially expected), and then it varies just slightly because of some decorative word painting. Sometimes listeners pick up on it and sometimes not, but performers (and musicologists!) do. I adore musical analysis, and that side of me loves finding a bit of surreptitious word painting in a piece – so it’s only natural I include some in my own music!

Here are a handful of word painting moments from Cracked Voices art songs (so far!). It’s only a brief selection of four – how many more will there be by the time the cycle is complete? All snippets below are taken from the vocal lines.

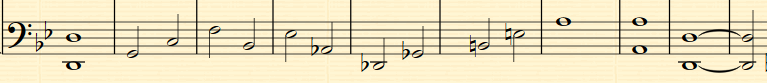

From The devil and the draper – a bit of hopping to begin the chorus! The melody hops up a third then another third, with bouncy staccatos in a rather quirky, bouncy time signature (7 8 being a personal favourite).

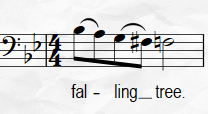

From Three riddles (no.2) – A falling tree.

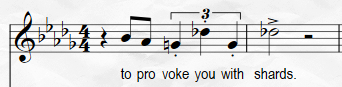

From Those who wait – shards are spiky staccatos (may turn into staccatissimos, or accented staccatos in the final version) to demonstrate their sharpness. The intervals between the words -voke, you, with and shards are all diminished fourths – a dissonant interval, uncomfortable to sing and commonly referred to as the devil’s interval.

The final excerpt is also from Three riddles (no.2) – an earthquake rocking the baritone’s line. Rock this place begins the rocking motion in triplets, followed a couple of bars later by a continuation of the rocking (yet downwards) motion.

Musical Easter eggs anyone?

“Here’s some words. Set them to music”.

A very simple instruction that has been issued to many a composition student over the years. I remember this being said, and the mixed response from my peers. Some had a song writing background and instinctively leapt in that direction, others took a more analytical approach and began looking at strong and weak beats, stresses and accents – annotating the text with a variety of symbols.

The art of writing an art song, however, is to remember that it isn’t just about setting a text. It’s about crafting a story. It’s forging the right mood and atmosphere, somewhat akin to the work of the impressionists, while still allowing the text room to be expressive in its own right. The role of the piano (and any additional instruments) is just as key as that of the vocalist, and that must be reflected in the music.

Speaking of the impressionists, we also have the whole world of techniques that previous composers have explored open to us. When we learnt about musical history in school, the vast majority of it is categorised. Renaissance, baroque, classical, romantic, modern/contemporary. You then get those in each period of music who are pushing the boundaries- increasing dynamic ranges, augmenting musical languages and exploring techniques dismissed previously. We’re now at a point where so much exploration has happened that there are now a wealth of techniques available to us to experiment with in our music – yet another element to consider when evaluating the atmosphere of an art song (or of any piece!).

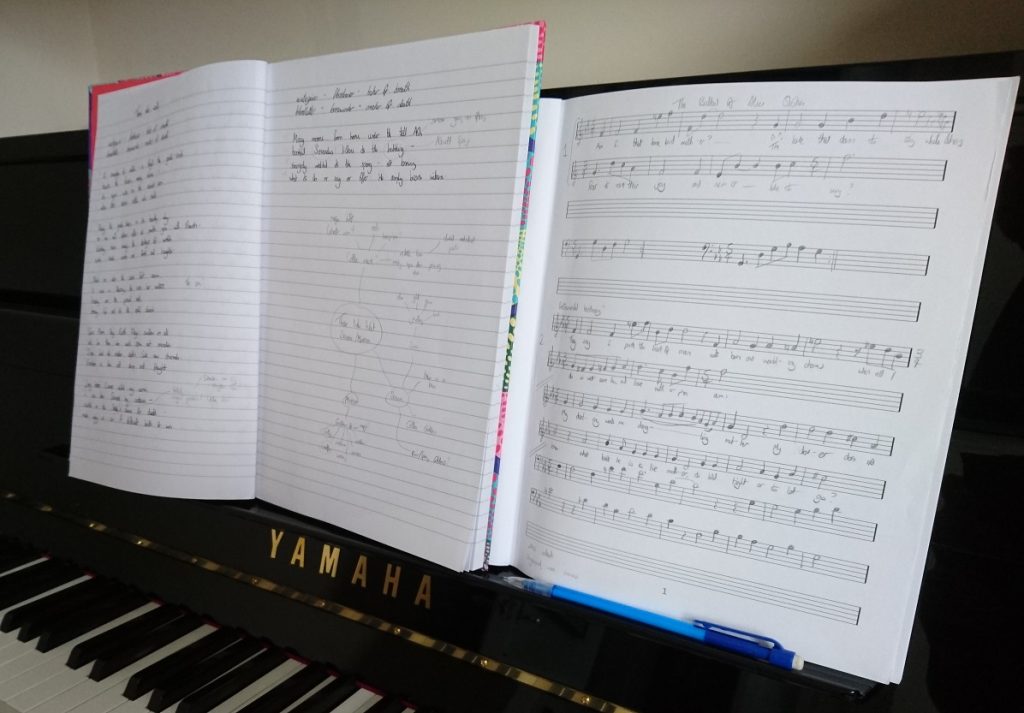

Different composers have different working processes. When Graham sends over a new Cracked Voices text, my first response (after reading it through a few times, naturally!) is to write or type it – normally both. I then start jotting ideas around it linking to specific moments in the text, whilst also creating a huge thought diagram around everything to do with the text – the story, the history, what’s said and what remains unsaid, imagery and atmosphere. Sometimes I’ll find that I know precisely what I’ll be writing (even to the point of hearing it in my head) after internalising the text, and the notes and diagrams serve as a method of consolidating and confirming everything in my head. Other times I’ll need to spend some time playing with these thoughts and expanding them until I hit upon the right thing.

Text, ideas and sketches at the piano. Includes a sneak peak at some Cracked Voices sketches!

The piece I’m currently working on is the opening song of the cycle – Those Who Wait, about the goddess Senuna. I wanted the atmosphere to be quite ambiguous tonally in the opening, while simultaneously relating to Senuna’s roots. When I realised that she was a Celtic goddness, the music snapped into place- open fifth chords (chords that aren’t either major (happy) or minor (sad) in quality, just ambiguous) combined with both them and the melody moving in a fashion similar to traditional Celtic music formed the perfect basis to begin the piece.

The accused witches have a piece that currently reflects their characters and their story. A slightly jazzy ballad scored in an unusual five crochets in a bar, the piece reflects a slightly relaxed tango, hinting at the merry dance they trod. The melody line features a few rather unusual leaps, and time changes make the piece feel a little unsettled, as Alice and her mother head towards their fate.

Both these pieces are still being fleshed out, but their musical foundations are already firmly rooted. The scenes have been set – it’s time to sing.

Last week Graham and Jenni were on BBC Radio Cambridgeshire’s Lunchtime Live, talking to Thordis Fridriksson about Cracked Voices! Listen again (for the next 10 days) on iPlayer Radio.

Let’s start at the very beginning! Before I start posting about how I’m composing some of the Cracked Voices pieces, I thought I’d talk a bit about art songs and their history.

To put it bluntly, an art song is a poem set to music. Traditionally they are secular, and feature a pianist and a singer. Sometimes they feature more than one vocalist – in our case, we’re using both a soprano and a baritone. More unusually, we’ll also be augmenting the setup with one further instrument, which is uncommon but not unheard of! They’re designed to be performed in a more formal setting, such as concerts and recitals, which differentiates them from musical theatre songs, folk songs and popular songs. Grove rather amusingly defines them as “a short vocal piece of serious artistic purpose” which makes them sound all too serious, but their subject matter be absolutely anything, be it humour or discussing death!

A song cycle, then, is a collection of art songs linked together. The link could be a very vague thread, or they could be intrinsically tangled together. Obviously the subject matter will be the predominant link in Cracked Voices, but there are others that I’m sure we’ll discuss later.

Some people are more familiar with the term lieder than art songs – the term more specifically for German polyphonic art songs. Schubert is historically the king of lieder, having written over 600 in his lifetime. I was introduced to a vast array of art songs at university (predominantly lieder!) when accompanying some wonderful singers for various workshops and recitals, which is where my love of them began. Below is a recording of one I’ve acccompanied several times – Schubert’s famous Erlkönig, complete with animation (and one of the few recordings I’ve seen that credit the performers). This was recorded by Oxford Lieder as part of their Schubert Project.

Various composers have written art songs in a multitude of languages. If you’re interested in finding some others, The Art Song Project have recorded a whole range, including a lot by living composers (and the one of mine below!).

One constant worry for all writers of new music is how do we draw new audiences in? Some audiences would find new music scary, and may be daunted by an evening dominated by a newly commissioned lengthy symphony. In a song cycle, however, each song tends to be short and sweet – averaging around three minutes in length (shorter than your average pop song!). Each of ours will have characters and a story behind it too, which when coupled with Graham’s wonderful writing will make these art songs excellent for anyone to sink their teeth into, whether they’re a music academic or a newcomer to the concert scene (and anywhere in between!).

In time I hope to share a few snippets of the Cracked Voices songs – sneak previews before the 2018 premiere! To give you a bit of a taste in the meantime, here’s an art song of mine composed back in 2013 – Bells in the Rain, performed here by Hélène Lindqvist and Philipp Vogler of The Art Song Project.

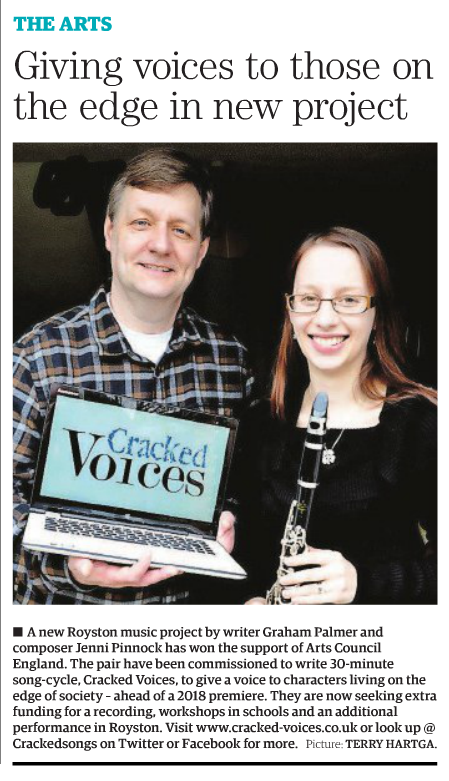

Thank you to the Royston Crow for covering our Cracked Voices project in this week’s edition!

Clipping of Cracked Voices from the Royston Crow

We’re also very excited to share that we’ll be on the local Arts&Ents section of BBC Radio Cambridgeshire’s Lunchtime Live on Monday 6th March, between 2pm and 3pm talking about the project.