The text is written. The dots are on the page. The rehearsals all completed, the performers walk on stage..

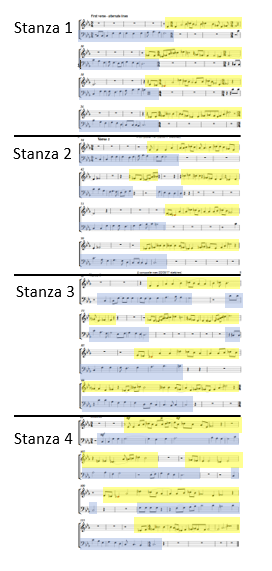

As Cracked Voices has progressed, Graham and I have shared snippets of our processes with you. From the beginnings of Graham’s research into a piece from me musing on inspiration and scales, we’ve given you an insight into how we work. Between February and October, 10 art songs were drafted, ready for rehearsal, having being shared between Graham and I. Before they could head towards the performers they had to be checked one more time and parts created. As anyone who has ever created parts in any scoring program can attest to, this is never as easy as pressing a button – there’s always further tweaking to be done before they’re ready for the performers to set eyes on them.

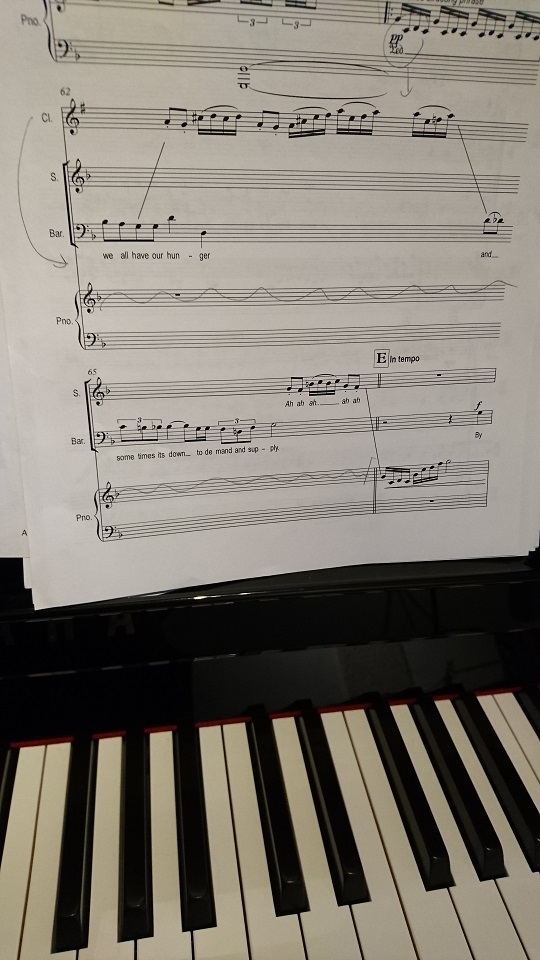

In November, it was wonderful to finally have Donna, Ian, Sue and Ralph in the same room and to hear them performing together. Some of the pieces required more rehearsal than others, but we managed to get through all 10 completed songs. While some pieces were fine as they were, others needed tweaking in various forms. Graham and I each came away with our own notes, along with those suggested by the performers, which we discussed before I began the next stage of redrafts.

This is what it looks like when the cat decides to knock all the pieces you’re currently redrafting off of the piano.

I then deliberately ignored the physical scores for a while and just listened to the recordings of the rehearsal. Which bits didn’t feel quite right? Where was the balance wrong? How could I convey Graham’s carefully crafted words better? I recorded the whole rehearsal on my handy H4N Zoom recorder (an invaluable piece of kit) so I could hear not only how the pieces were performed, but also re-listen to our discussions about them in case I’d missed anything vital.

It was then time to get back to work. Some pieces needed more work than others. For example, for A composite man, it was decided another part was needed to tie the vocal parts together. The clarinet, then, became the spirits of the dead workers and widows. Other pieces needed more bird song, or less accompaniment.

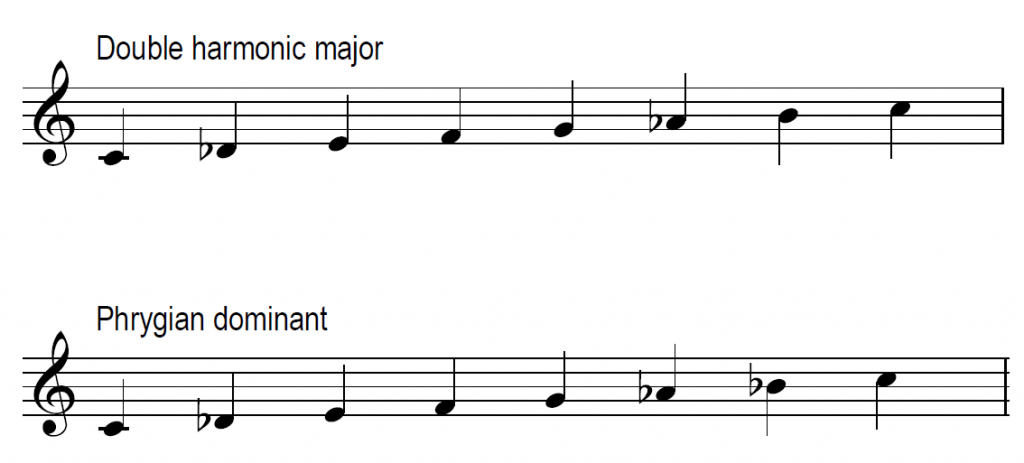

The process of redrafting is always a tricky one. You listen, analyse, revisit and revise, time and time again. Often you find yourself amending a line in one fashion one day, only to amend it back to the original the next. Along with the changes to actual notes, lines and instrumentation in the redraft stage, there are also the more technical bits of music notation. Which time signatures convey the music best and ensure it makes the most sense for the performers – a non-standard beaming of 12/8 or 6/8 followed by 3/4? Should I spell my phrase F sharp – F natural – F sharp or should it be an E sharp in the middle – or G flats at either end? I’ve found that with Cracked Songs a considerable amount of this stage has been spent playing around with these nitty gritty bits. Not only do you have to make them make sense throughout one song, but the whole cycle has to be taken into consideration too – it has to make sense as the sum of its parts as well as each constituent piece, and in the way it is notated along with the actual music itself.

Tweaking scores to ensure they’re as clear as possible is always a priority. If they have to puzzle over engraving they can’t immerse themselves as fully in the music.

I’ve spent the month and a bit since the rehearsal tweaking and redrafting – and I’m just reaching the end of the process. In the next few days the ‘final’ version of the scores and parts will wing their way over to the Cracked Voices performers, ready for them to look at for the next rehearsal. Along with polished final versions of the previous drafts there are two new pieces – the final two songs of the cycle.

That double bar line really is only the beginning.